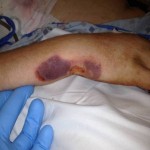

M. Aziz, a 52-year-old male Afghan civilian, sustained a right tibia shaft fracture, a left tibial plateau fracture, and a left subtrochanteric fracture after driving over an improvised explosive device while on his way to visit his brother.

Question: How would you address these closed injuries in an austere environment with only external fixation available for definitive treatment?

“I used external fixation for the right tibial shaft fracture. It was an easy, straightforward procedure,” explained Aziz’s surgeon.

The damage to the left side was more complicated. “I was running low on external fixation connectors, pins, and rods with the case, so I decided to use the distal femur pins in both the left spanning knee fixation and the left hip fixation,” said the surgeon.

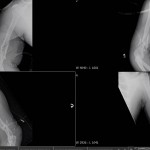

As the operating room does not have a fluoroscope, prior to surgery the surgeon places a radio-opaque marker next to a mark he makes on the patient’s skin or next to an entry wound, such as a bullet hole. He then uses images from his own camera to determine where to place the pins based on the relationship of the marker to the patient’s anatomic landmarks.

“One trick I like is to place a flat plate under the hip before the patient is prepped. That way, after inserting the first pin blind with no C-arm, I can take an X-ray and check a plain film to see what adjustments need to be made and where the second pin should be placed in relation to the first. This saves a little bit of time, as we do not have to wait for a plate to be placed.”

In Aziz’s case, the surgeon did not want to place two additional pins in the patient’s femur. He was running low on external fixator pins and wanted to reduce the number of pins placed, since the patient already had multiple pins placed. The surgeon used the same pins in the distal femur for the hip and proximally for the spanning knee fixation.

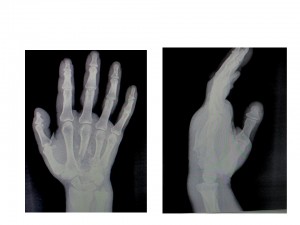

First, he stabilized the knee so that construct could be used to reduce the hip once the proximal pins were placed. For reduction of the knee, the surgeon pulled in extension, allowing for slight flexion of the knee. He “cheated” valgus a little past what he believed was aligned, as he did not have a C-arm in the operating room and had to use plain films to verify each reduction attempt (these injuries have a tendency to fall into varus), and was successful.

For the hip, the surgeon pulled longitudinal traction distally and “did the opposite of what the proximal fragment wants to do.” He extended, adducted, and internally rotated the proximal fragment to achieve reduction and again, it worked. For a final check, he consulted the X-ray.

“When I do the reductions I tighten one set of connectors and then perform the reduction with my assistant ready to tighten the second set. For the knee I tightened the proximal first and then reduced and tightened the distal. For the hip it was the opposite,” the surgeon explained.

Aziz required no blood products during surgery. Within one hour of the surgery being completed, the dust-off crew medevaced him to a civilian hospital. He was transferred in stable condition.